More Practical Issues in Career Effectiveness: Thick and Thin Leadership

In 1980, VOLUNTEER: The National Center for Citizen Involvement (predecessor of the Points of Light Foundation) published Exploring Volunteer Space: The Recruiting of a Nation, by Ivan H. Scheier. As has been the case so often with Ivan’s writing, the book was way ahead of its time. This excerpt may have lots of outdated references, but the concepts are as fresh as ever.

Volunteer leaders sometimes express...an apparent yearning for work‑related schizophrenia: the ability to be two people at once, in five places at once, doing ten things simultaneously. In other words, 70,000 volunteer directors for 40 million volunteers are a thin line nationally, and sometimes the same is true for individual volunteer program efforts. While this is not always so, generally the overwork syndrome is unfeigned. There are too few volunteer directors or coordinators today for the number of volunteers they have or should have. The resources of Voluntary Action Centers and other clearinghouse operations are typically strained for their mission of community mobilization.

Translating Knowledge

Volunteer leadership must be concerned with the translatability of hard-won skills and knowledge over the larger reaches of volunteer space. This concern applies whether the new volunteers are actually in your program, across town when you want to coordinate with them, or represented at a national conference where you would like to feel at home.

Recently accepted inclusions in the total volunteer constituency are Board or policy-making volunteers, and to a lesser but still significant extent, issue-oriented volunteers. It is no longer remarkable to find on an agenda for a workshop attended by volunteer service directors such items as advocacy, policy (boards), client volunteering, the development of skillsbanks (occasional service), and self-help and informal networks as species of citizen participation. Along with the agenda items, you will also find at the workshops the people who are doing these things. Our core volunteer concept knowledge seems to translate and transfer to leadership of volunteers in these outward ranges of volunteer space, and we seem able to learn from them, too. I personally presented each of these perimeter topics several times last year, sometimes several of them in the course of a single conference. I know other trainers have had similar experiences....

The point is, we whose origins are in traditional service volunteering can credibly transpose those skills and knowledge to far wider volunteer spaces and we can have this knowledge accepted there. We must only make an effort, be willing to be rejected now and then, and be willing to learn from the present occupants of the other spaces. Even when translation is less than total, cross-fertilization will still be a benefit. Indeed, we are only beginning to discover the different, but not too different, things self-helpers know that we could use; the same could be true of Board and network experts. If we are open enough to learn as we teach, and interact as we act, our entire store of ideas and methods will be enormously enriched, and the commonality of knowledge and language will build further roads through a total helping territory.

Meanwhile, I'm not sure anyone can yet itemize all the competencies generic to leadership through all volunteer space. Pending further forays into the area, general competencies probably include the following. First, we have the skills needed to motivate people without money, and keep them motivated. Sub-headings here might include the ability to access what people really want to do and minimally mold these desires to larger group purposes. Also of value is some mastery of a leadership style which is more encouraging than demanding, more enabling than coercive. Ability to communicate with essentially part-time workers is crucial, as is the ability to coordinate a relatively large set of part-time efforts.

Through it all we need understanding of the practical psychology of motivation. Frequently but not always, we also require some understanding of applied sociology, organizational behavior, and cultural anthropology. Other topics volunteer leaders study today, though they have never been unique to the volunteer leadership field, are power, public relations, fund‑raising and community resource development, and how to facilitate the learning/training process.

Career Mobility

We have a formidable burnout rate among career leadership, especially among new directors and coordinators. When asked to speak about this at workshops, I usually prescribe a clear upward mobility track, however individual directors choose to define it in terms of increased status, responsibility/challenge, money, or any or all of these. I then proceed to explain why this upward mobility is virtually impossible.

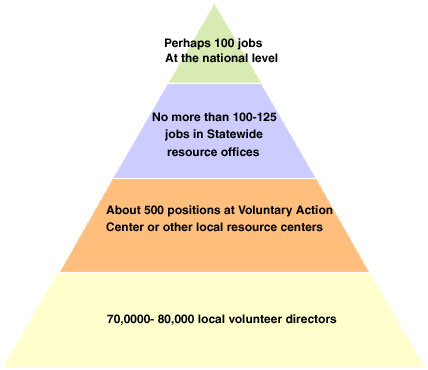

One somber illustration of this sad situation is the career pyramid. It assumes that a person wants to stay quite strictly in the field of volunteer administration, and it looks something like this:

The actual pyramid is much more forbidding than the diagram indicates. Roughly speaking, the chances of a local volunteer director getting a job in the upper echelons as defined here are about 100 to1 against, or worse. Local, state, and national offices often do not recruit employees from the ranks of local volunteer directors.

For all practical purposes, the only meaningful mobility is horizontal, or at best, diagonal. One moves over to a related occupation and one hopes this means up at the same time. These related occupations are, of course, leadership roles in neighboring parts of volunteer space; from volunteer coordinator to staff in a community action group, for example.

There is obviously an intimate relation between transferability of knowledge across volunteer space and overall upward mobility in leadership careers. As we identify and develop the common ground between service programs, and such efforts as self-help, skillsbanks, advocacy volunteering, board development, and neighborhood mobilization, career scope and maneuverability increase for all leadership persons in the people involvement field.

Coordinating Helping Tactics and Strategies

The same increased maneuverability will mean something to those who stay in place, wanting to do their caring jobs better and feeling hemmed in by the inability of any single organization or effort to do the total job. For this leader, a more effective communication across wider reaches of volunteer space opens up a rich variety of tactical alternatives. When you are comfortable and credible in a more inclusive sphere of volunteering, there are more arrows in your quiver, more ways to hit any target.

Suppose we wish to attack a set of problems in a neighborhood. The traditional director of volunteers might have the instrumentality of an organized or agency-related service program pertinent to the problem area. This will help, but it is unlikely to solve all the problems. Suppose now, in the same situation, you were a community participation facilitator, with access to wider volunteer space, and that the problem was community crime prevention. You now have more than one volunteer instrumentality to work with. Theoretically, at least, you can engage and orchestrate a number of positive participation modes related to the problem: volunteer probation officers working in that neighborhood; volunteers with victims; a block watch effort (occasional service via observation); various volunteer study, policy-setting, and advocacy groups; ex-offenders or offenders as volunteers; a police athletic league, and so on.

Moreover, volunteer service programs might increase the net effect by collaborating with, for example, self-help groups or individuals, with community helping networks, community study groups and boards, in a coordinated attack on the problem. As neighborhood volunteer facilitator, you would be far more effective in weaving the fabric of solutions if all the threads were in your hand. And, as indicated before, there is real evidence that the volunteer director can be helpful, credible, and accepted in this wider volunteer space.

No one ever said it would be easy. First of all, most volunteer directors and related volunteer leadership work for a single agency or organization today. The broader administrative setting and base for coordinating wider volunteer space is not ordinarily there, not officially at any rate. Nevertheless, there is promising precedent. I've occasionally encountered the title "community volunteer coordinator" or its like, in rural areas, and some Voluntary Action Centers and self‑help community resource centers are clearly moving in this direction. At the very least, some sort of community involvement committee should be possible, in which each volunteer leader would represent his/her organization as well as the community or neighborhood at large. The North Carolina Governor's Office of Citizen Affairs is actively encouraging this kind of total community coordination, and receiving excellent local response in so doing. [See Getting Together: A Community Involvement Workbook, (Raleigh, N.C.: The Governor's Office of Citizen Affairs, 1978).]

Agency turf will probably be the primary problem in delaying horizontal community-based citizen involvement, as distinct from agency-segregated models. Exploration and development of common themes throughout volunteer space in all agencies and organizations, should help to erode such turfdom. Thinkers have always said the volunteer was uniquely fit to be a linker, with primary loyalty to the community rather than the agency. Someday we are going to have to reflect that potential in the way we organize volunteers, or else leave them innocent of our organizing efforts.

Being Powerful

Let us speak of power for a moment and its purposes for us. These purposes include fostering an increasing awareness of the value of volunteering, and upgrading the dignity and support accorded volunteer work and the work of volunteer leaders. Let us further consider that important variety of power which lies in numbers. This in turn brings us to a final advantage of exploring volunteer space. More ultimate than immediate, we have the potential for developing a broader, more varied constituency for volunteering itself, composed of volunteers.

It has always struck me as odd that virtually all our efforts to mobilize advocacy for volunteering have been oriented towards organizing career volunteer leadership – a significant but relatively miniscule group, or else advocacy has depended on the work of a very few resource organizations, notably the Washington office of VOLUNTEER: The National Center for Citizen Involvement. By contrast, there are about forty million volunteers in the United States , and even a million – or ten thousand – would help. As we promote citizen participation, legislators at the state and national levels will listen more carefully when we have more votes at our back.

Exploring volunteer space should yield a larger and more representative group of volunteers among whom we can organize. Some of the new volunteers will already be advocates and policy developers, and perhaps they can be persuaded to advocate for the process by which their advocacy occurs (volunteering) as well as for the purpose of their advocacy.

Among my proposed (and rejected) ideas for this type of advocacy effort appear titles like the Volunteer Guild (1970), the National Organization for Volunteers‑America (NOVA, 1975), and the League of Volunteers (LOV, 1977). More recently, my friend Paul Weston suggested a better name – the American Volunteer Association; he also suggested that the association be affiliated with national resource and professional groups in the volunteer leadership field.

Though there are those who insist volunteers will never organize, it has been done, in part. The number of volunteer advocacy organizations already in existence range from relatively small but significant ones such as The Independent Foundation (ex-VISTA and Peace Corps volunteers) and the newly-formed National Association for Volunteer Action to huge pools of volunteers in such groups as the National Congress of Parents and Teachers, the Parents of Retarded Children, the Jaycees, the League of Women Voters, and Call for Action, and in political parties. Some of them show significant awareness of volunteering as a cause, beyond the specific causes for their volunteering. The Association of junior Leagues, for example, is an effective advocacy force for volunteering in general.

A system could be devised linking such groups to vote together on issues of general concern for volunteers. (There would almost certainly be a different set of groups choosing to ratify each proposal brought to the coalition.) This linkage system would be a realistic start for an American Volunteer Association. As volunteer space expands, there would be more groups "eligible" to participate in its volunteer advocacy linkage system. Volunteer leadership would significantly benefit from the existence of this constituency, and so would volunteers.

There is another reason for attempting a volunteer coalition. Volunteer directors and other volunteer leaders sometimes speak as if they were elected to speak for volunteers. Rarely is this true for volunteer directors (though it's usually true for club leaders and sometimes it's true for clergy). But volunteer directors are usually hired by people other than "their" volunteers, though they listen carefully to their volunteers and try to speak for them. A genuine association of volunteers would give us a more authentic process for hearing what they say, being responsive to it, and truly representing it. I also believe that out there in the newer regions of volunteer space are many more volunteer-related people – advocates, policy volunteers, informal or non-program volunteers – who will insist on this responsiveness. Volunteer leaders will be stronger for having listened.